For some reason in I decided to only read short books this month. By this I mean novellas, small books of essays and flash fiction. It worked out very well but did leave me gagging for an epic novel, which on the 1st of December I reached for immediately.

Anyhoo…here’s how I got on with my reading during November :

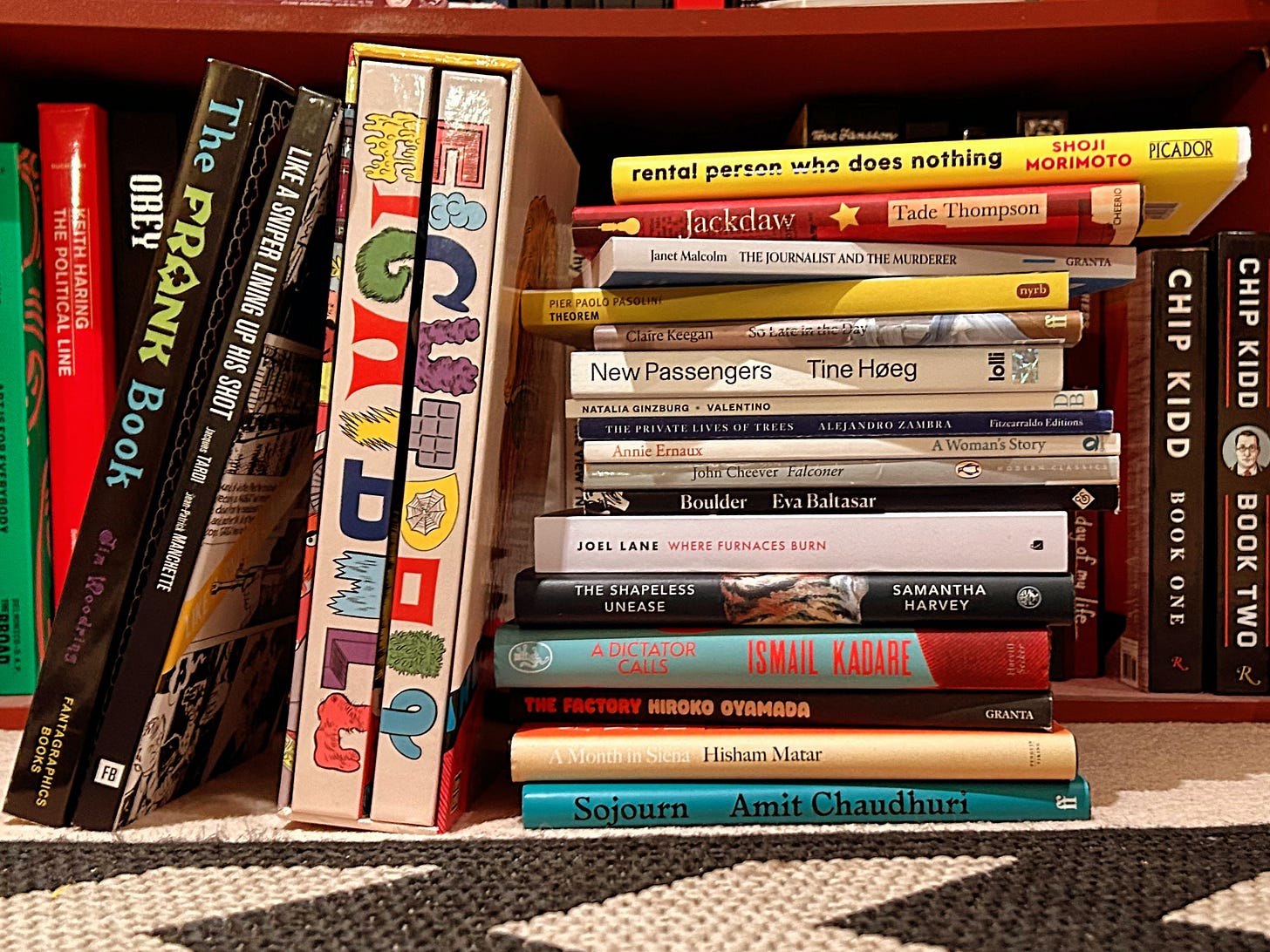

“Yesterday I rented Rental Person. I asked him to be another me. I'm too busy to do everything I want to with just one me, so I created another. This other me went to Nishiya Coffee Shop and had the crème caramel I've always wanted. I'm so happy! (I'll go myself one day.) This other me was very nice! She bought a book for me I'd always wanted and even brought me a present. I'd asked her to take photos through the day. Some were of a cafe she recommended. I'd never heard of it, but I'm looking forward to going there sometime. I'll go to LOFT lifestyle store too and have a great time like every girl student should. In the early evening, I met up with myself in Ikebukuro and heard a bit about my alternate day. We both like to concentrate on eating so we didn't talk too much. I felt a bit of a generation gap, but it was fun. After we'd finished, my real me gave my alternate me - Rental Person - some flowers. This was something else I really wanted to do. The kasumisou I happened to pick up in the florist are symbolic of gratitude, apparently, so that was just right. Thank you very much, Rental Person, for everything.” - from “Rental Person Who Does Nothing : A Memoir” by Shoji Morimoto. (Picador. 2023)

“Of course, the amount of money people are paid for work (in my case, writing fees) depends on the market and no account is taken of the stress involved. This didn't feel right to me. It seemed unfair that people who wanted to do the work, and didn't feel at all stressed by it, got paid the same as people who didn't want to do it and did feel stressed by it. It seemed wrong that I was getting nothing for the mental burden the work was giving me. I can imagine people muttering to themselves, 'Well, there's no such thing as an easy job', and I fully appreciate that there's nothing unusual about work stress. But even so, the situation really bothered me.” - from “Rental Person Who Does Nothing : A Memoir” by Shoji Morimoto. (Picador. 2023)

A fascinating, surprisingly wholesome look at a man who has managed to turn his skill at “just being” into a sort of back to front job. His whole view on his role in peoples lives, not just as a neutral onlooker but also as a catalyst and non judgemental company was so interesting, and full of unexpected things.

A unique addition to the literature about work and the people who do it or in this case don’t do it. A real, odd, heart-warming book.

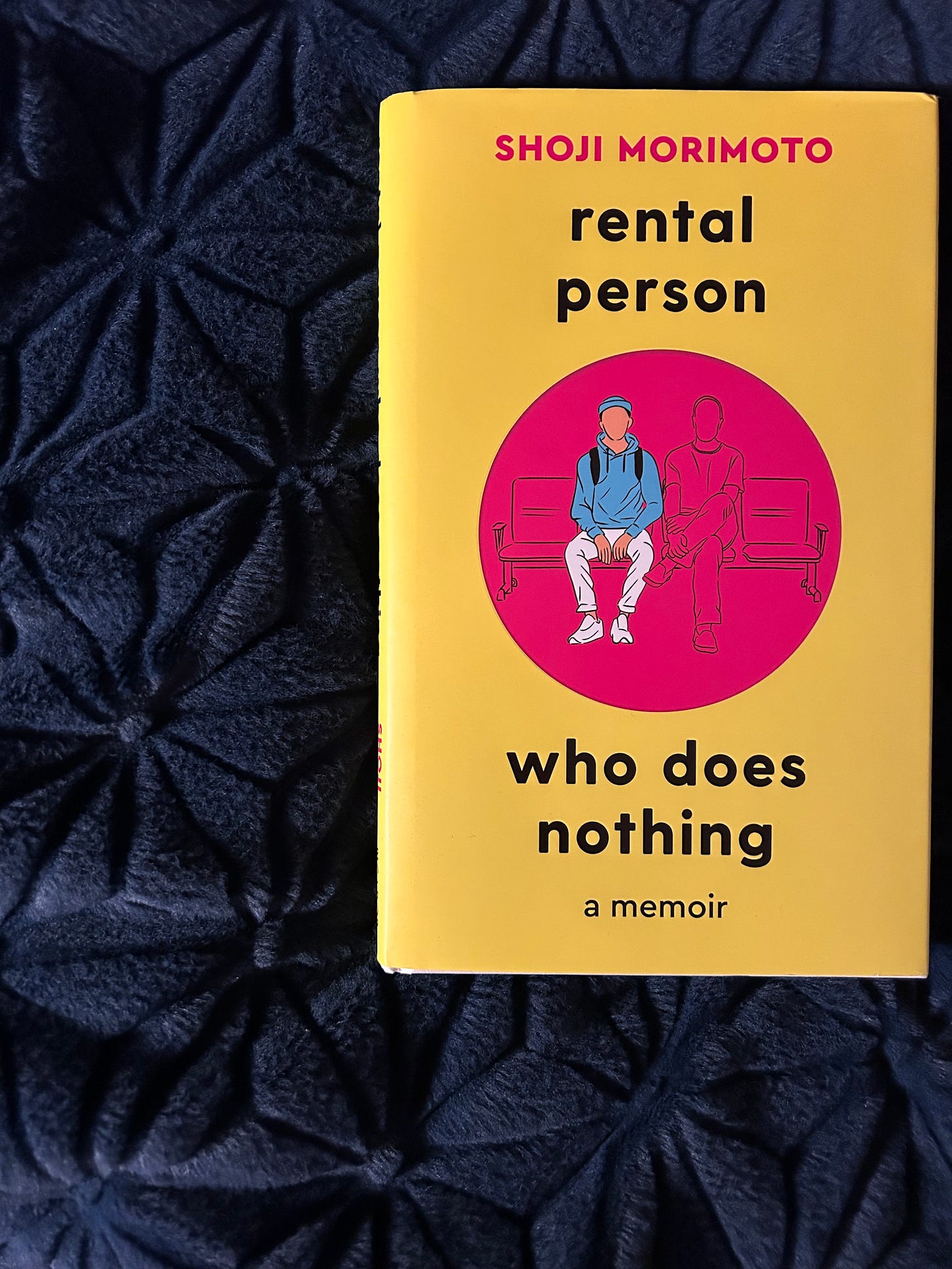

“I am going about my business, the business of art, something which you, with your shock-troop mentality, cannot comprehend. I am making myself into something new, a living sculpture, a breathing installation, work after a master of the form. I am living slime, living excrescence from the moist junction of living beings. I am life itself, or the residue of life that is left after my passing. That is what I'm trying to do, to accomplish, don't you see? I don't know why I'm talking to you. This is not the kind of digestible creation you ingest, is it? You like potboiler paperbacks, coffee adverts and car commercials, don't you? Reality-style shows? When were you last in a museum or gallery? When did you last read a book that wasn't fiction? Do you see why it is futile to stop me, to interrogate me? I am floating above all this. I made all this, but not in my own image.” - from “Jackdaw : Being the memoir of a most interesting assignment”by Tade Thompson. (Cheerio. 2022)

Gleefully meta, but perhaps a bit too gleeful.

Fiendishly crafted, but perhaps a bit too fiendish.

Definitely a very interesting piece of work but definitely not, to my mind, completely successful.

Having said this though it's worth noting that "Jackdaw" runs down a transgressive literary road less traveled and Thompson somehow manages to not let its annoyingly knowing, smart-arse tone ruin the overall experience and narrative thrust, a feat in itself.

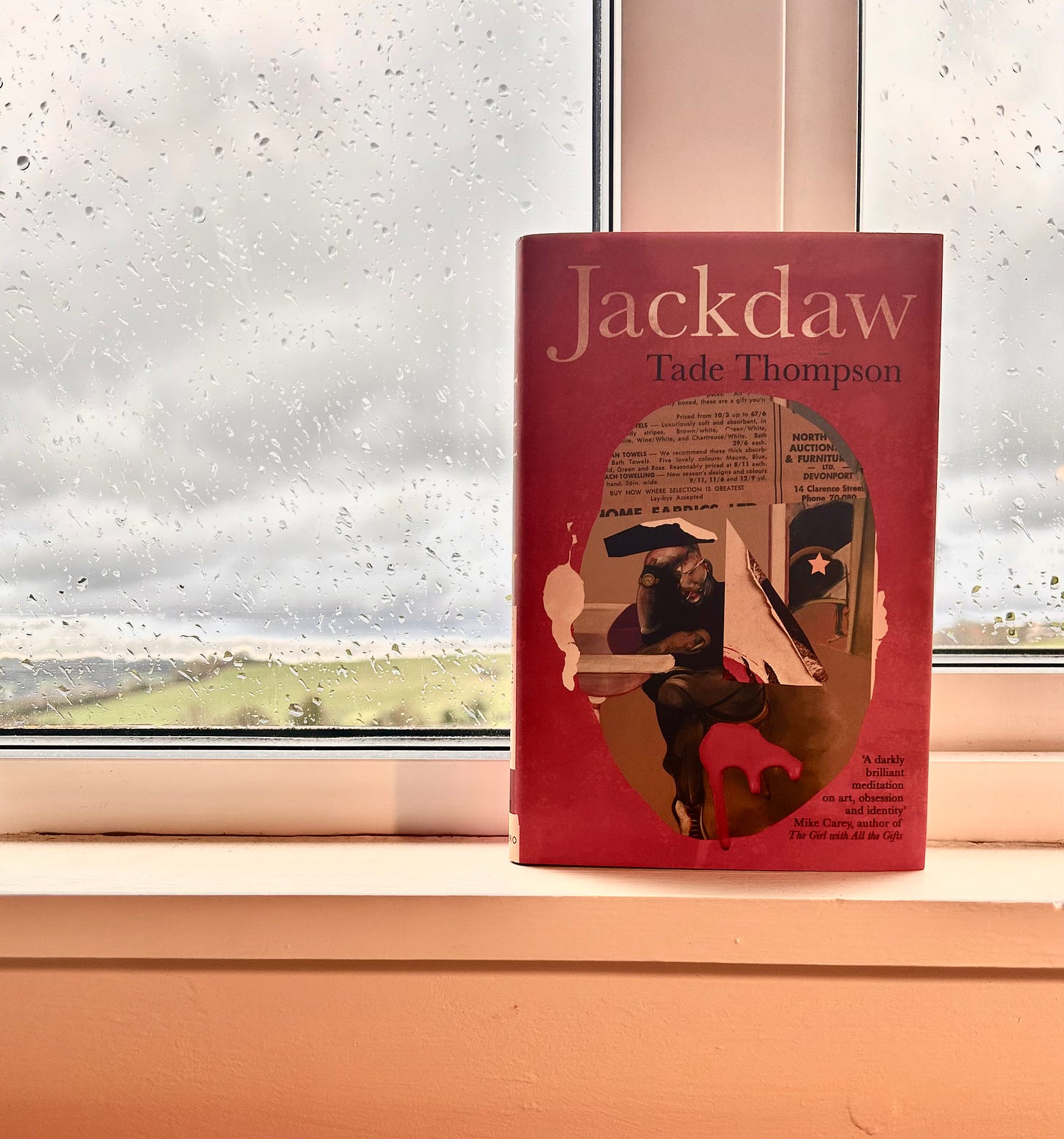

“Unlike other relationships that have a purpose beyond themselves and are clearly delineated as such (dentist-patient, lawyer-client, teacher-student), the writer-subject relationship seems to depend for its life on a kind of fuzziness and murkiness, if not utter covertness, of purpose. If everybody put his cards on the table, the game would be over. The journalist must do his work in a kind of deliberately induced state of moral anarchy.” - from “The Journalist and the Murderer” by Janet Malcolm. (Granta. 1990)

A provocative look at the legion of problems and the unavoidable but irresistible consequences of the subject-author relationship, drawn from one of the most convoluted and contentious murder cases of the 80’s.

I love books about the slippery nature of perceived truth and I find our need to expose ourselves to the critical facilities of others endlessly interesting, if you think on these things too, you need to read this brilliant book.

Nobody can come out of a deep, supposedly subjective analysis smelling of roses, but our continued need to give out undeniably intimate details to supposedly sympathetic people remains undimmed, even though the evidence suggests this relationship hardly ever works out well.

“Like the young Aztec men and women selected for sacrifice, who lived in delightful ease and luxury until the appointed day when their hearts were to be carved from their chests, journalistic subjects know all too well what awaits them when the days of wine and roses, the days of the interviews, are over. And still they say yes when a journalist calls, and still they are astonished when they see the flash of the knife.”- from “The Journalist and the Murderer” by Janet Malcolm. (Granta. 1990)

“It seems incredible that the night can be so lifeless and so full of the lifeless desire to be so. Yet, who knows how, at the bottom of the abyss of the mist clinging to the earth, beyond the vapours that drift over the roofs and the tops of the poplars, beyond the torn low bank of cloud and, finally, beyond the boundlessly high clouds, the guarantees perhaps of fine weather the next day, one glimpses a sliver of moon as thin as a slice of lemon or pumpkin: a moon that is setting and going away, unobserved and defeated.”- from “Theorem” - Pier Paolo Pasolini. Translated from the Italian by Stuart Hood. (NYRB. 1968)

Pretty wild stuff here from the maverick Italian polymath and undeniable genius Pasolini. Written with no timeline, in a purely objective present tense "Theorem" was meant to be read as a poem but changed into something more like the effect of looking at a fresco, an effect of ever shifting surfaces, telling a ongoing, wilful narrative.

Somehow PPP pulls this off with a heavy dose of political commentary, sexual transgression and undeniable beauty.

Strange, baffling, deeply stimulating.

“Why are caravans called things like Pegasus, Sprite, Unicorn? Never a less sprightly thing did I ever see than the great off-cube of a caravan wobbling unaerodynamically along the slow lane on its tiny narrow wheels. It's like calling a shopping trolley Icarus, Voyager, Swallow.”- from “The Shapeless Unease : A Year of Not Sleeping” - Samantha Harvey. (Jonathan Cape. 2020)

Insomnia is a private, individual, self feeding horror that has been with me whenever it feels the need to take over since the sudden and total breakdown of my parents marriage forced me to acknowledge, at the age of 14, the gaping maw of chaos that exists under every crust of comfort and normalcy.

“Think of a sentence: One day I'd like to write a story about a man who, while robbing a cash machine, loses his wedding ring and has to go back for it because his wife, a terrifying individual whose material needs have driven him to crime, will no doubt kill him if the ring is lost.”- from “The Shapeless Unease : A Year of Not Sleeping” - Samantha Harvey. (Jonathan Cape. 2020)

There’s a lot of shame and misconceptions attached to not being able to sleep so most who suffer from it keep it to themselves until it’s impossible not to cope anymore, and even then, as written about here, doctors, psychologists, those who sleep, find it hard to scrape together any empathy for your condition.

“What a thing this is, to be so firmly entrenched in the here and now. What a thing. We are, I am, spread chaotically in time. Flung about. I can leap thirty-seven years in a moment; I can be six again, listening to my mum singing while she cleans the silver candelabra she treasures, that reminds her of a life she doesn't have. I can sidestep into another possible version of myself now, one who made different, better decisions. I can rest my entire life on the cranky hinge of the word 'if'. My life is when and until and yesterday and tomorrow and a minute ago and next year and then and again and forever and never.”- from “The Shapeless Unease : A Year of Not Sleeping” - Samantha Harvey. (Jonathan Cape. 2020)

Samantha Harvey understands the madness of insomnia and writes about it with tremendous courage, brutal self awareness and a sideways beauty that anyone would identify with, not just the closed but undoubtedly huge membership that is the sleepless.

Magnificent.

“Then a week later when the test results come back normal it points towards what I already know, which is that my sleeplessness is psychological. I must carry on being the archaeologist of myself, digging around, seeing if I can excavate the problem and with it the solution - when in truth I am afraid of myself, not of what I might uncover, but of managing to uncover nothing.” - from “The Shapeless Unease : A Year of Not Sleeping” - Samantha Harvey. (Jonathan Cape. 2020)

“So there is no one to whom I can speak the words that most need to be spoken, about the events which most closely concern our family and what has happened to us; I have to keep them bottled up inside me and there are times when they threaten to choke me.”- from “Valentino” by Natalia Ginsburg. Translated from the Italian by Alexander Chee in 2023. (Daunt Books. 1957)

Another sublime Ginzburg making this the 3rd one I’ve read this year and definitely securing Daunt’s ongoing work at re publishing her work one of THE literary events of recent years.

She creates such a specific environment and energy, her sensibilities regarding what to include and what to leave out when describing the algebraic structures of human interactions, complications and predictabilities is a thing of great wonder and joy for me.

“I see him there, mooching about the flat in his tatty dressing gown, smoking and doing crosswords, he who my father always believed was destined for greatness, he who has always taken from others with never a thought of giving anything in return, he who has never neglected for one day to pamper his curls in front of the mirror and smile at his reflection; he who most certainly did not omit that mirrored smile on the very day of Kit's death.” - from “Valentino” by Natalia Ginsburg. Translated from the Italian by Alexander Chee in 2023. (Daunt Books. 1957)

“On Friday, July 29th, Dublin got the weather that was forecast. All morning, a brazen sun shone across Merrion Square, reaching onto Cathal's desk where he was stationed by the open window. A taste of cut grass blew in and every now and then a close breeze stirred the ivy, on the ledge. When a shadow crossed, he looked I out; a gulp of swallows skirmishing, high up, in camaraderie. Down on the lawns, some people were out sunbathing and there were children, and beds plump with flowers; so much of life carrying smoothly on, despite the tangle of human upsets and the knowledge of how everything must end.” - “So Late in The Day” by Claire Keegan. (Faber. 2023)

The huge commercial success of Claire Keegan’s incredible work is one of the more gratifying and but puzzling occurrences in recent years. From a bookselling point of view, seeing her work pass over the counter thousands of times, into the hands of people that 10 years ago wouldn’t have even considered reading something this powerfully stripped back, this pregnant with multiple meanings, is for me a source of great pleasure, having been a champion of her books ever since 2007’s staggeringly good “A Walk in Blue Fields.”

I find it hard not to wonder what it is about her work that has managed to breakthrough into a British mainstream not that known for embracing low page counts, liminal spaces, unsaid tensions and granite hard truth, a thing all fans of that certain stripe of Irish literature will be no stranger to. Maybe it was the lockdown years and how it shifted our sense of time and space that has helped this work become so popular…who knows.

A true master of “the line” her most recent fragment, initially published only in France under the title “Mysoginié”, is a devastating, but subtle examination of the endemic nature of inherited hatred of women, told beautifully with her trademark weighted brevity, “So Late In The Day” probably would not have been published on its own if this country (it was published in America and Europe as a part of a trilogy of stories about men and women) if we were not so desperate for new Keegan product, the page count and font size here barely justifies it, but of course the content is exquisite.

How does she do it? Who knows. As long as it continues to this standard I don’t care!

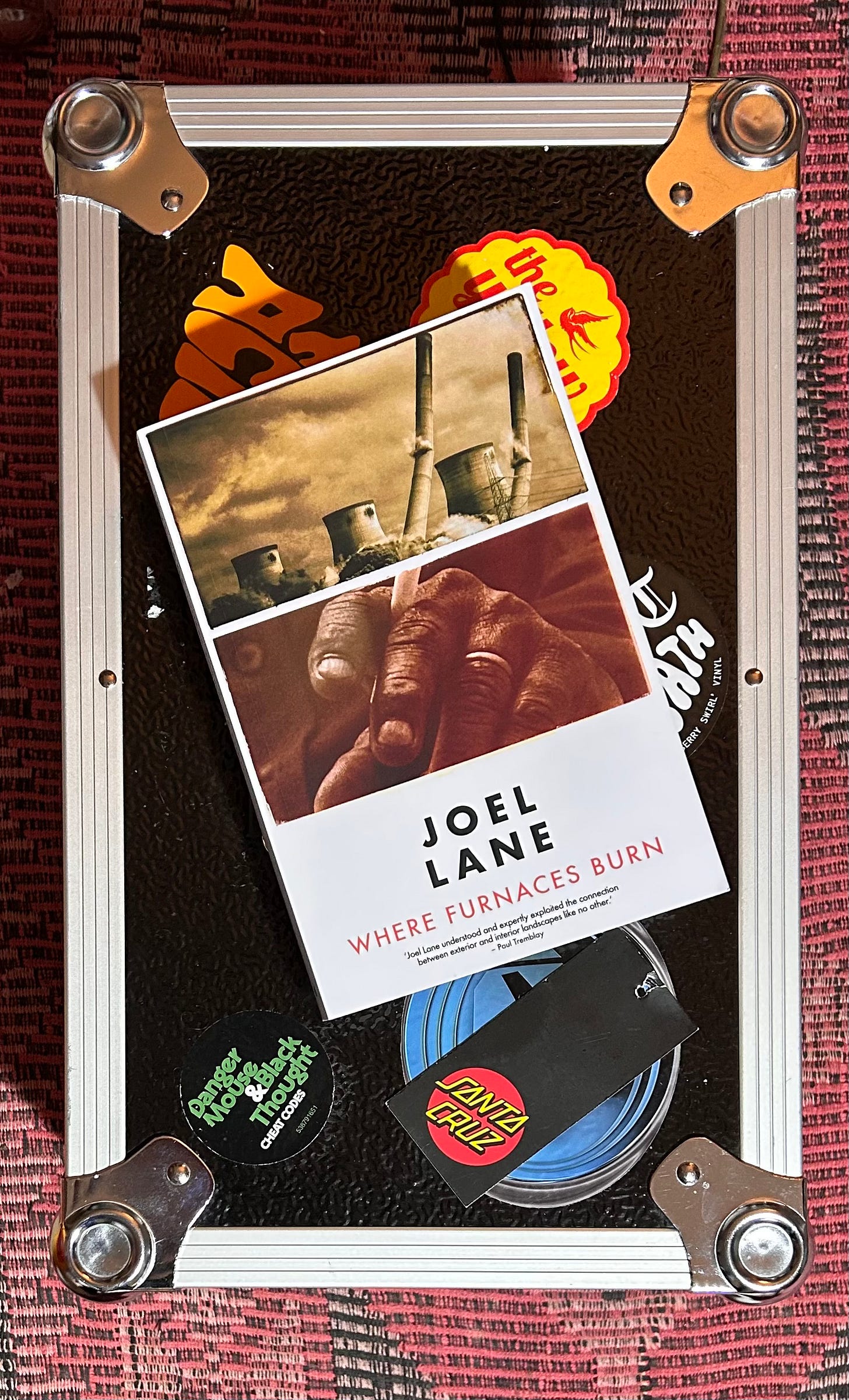

“A voice behind me said: 'In the next world, the snow is vodka. The rain is gin, the dew is wine. Come with me, I show you how to find it. I turned my head. A short man, either bald or with a shaven head, was staring at me. His eyes were so dark they could have been missing.”- from “Where Furnaces Burn” by Joel Lane. (Influx. 2023)

Set in the post-Thatcherite wastelands of the West Midlands; Birmingham, Walsall, Dudley, Digbeth, and Joel Lane’s bleak song is one of eternal winter, rotten bricks, the madness of far-right politics, the festering skull beneath the skin, the destitution of a relentless and absolute loss of all hope, so not exactly a barrel of laughs, but don’t let that put you off, this guy could really write the words down and his vision although barren of any light at all is nonetheless totally all encompassing and very gripping.

The fine folks at Influx Press have been beautifully reissuing his work and I will certainly be investing in the other books once I’ve recovered from this one.

“Terry was kneeling by the gutter. He wiped his mouth and stood up. 'Follow me, the monk said. 'I'll show you the blue light, the light hidden from the world. His lips weren't moving, but I could hear his voice clearly in my head. Terry looked at me, nodded. The monk turned and led us away from the high street, towards the end of the road. My breath was freezing on my lips. I felt sure this was a journey I wouldn't return from. It didn't matter.” - from “Where Furnaces Burn” by Joel Lane. (Influx. 2023)

Making a hitherto unestablished connection between the brutal industrial noir of David Peace’s “Red Riding” quartet, Derek Raymond’s “Factory” novels and then some creeping cosmic horrors of H.P. Lovecraft, this collection of interlocking short stories has been a reading experience that I won’t shake off in a hurry.

“But this is not a normal night, at least not yet. It's still not completely certain that there will be a next day, since Verónica isn't back yet from her drawing class. When she returns, the novel will end. But as long as she is gone, the book will continue. The book goes on until she returns, or until Julian is sure that she isn't going to return. For now, Verónica is absent from the blue room, where Julián lulls the little girl to sleep with a story about the private lives of trees.” - from “The Private Lives of Trees” by Alejandro Zambra. Translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell. (Fitzcarraldo Editions. 2023)

A writer of justifiably heavyweight reputation who until now I’ve not read but who I will certainly be reading more.

Masterfully controlled, constructed in two inverted cones of flowing, occasionally real time, occasionally overlapping narrative, this tiny but mind bending erotic almost fairy tale sums up much of the unspoken mysteries of connection, landscape, family history and coincidence in a way scarcely tapped.

Again underlining how the Spanish speaking world holds the key to what’s truly “fantastic”, this will definitely light the candle of anyone who likes Yuri Herrera, Eva Balthasar and the more prosaic edges of Mariana Enriquez.

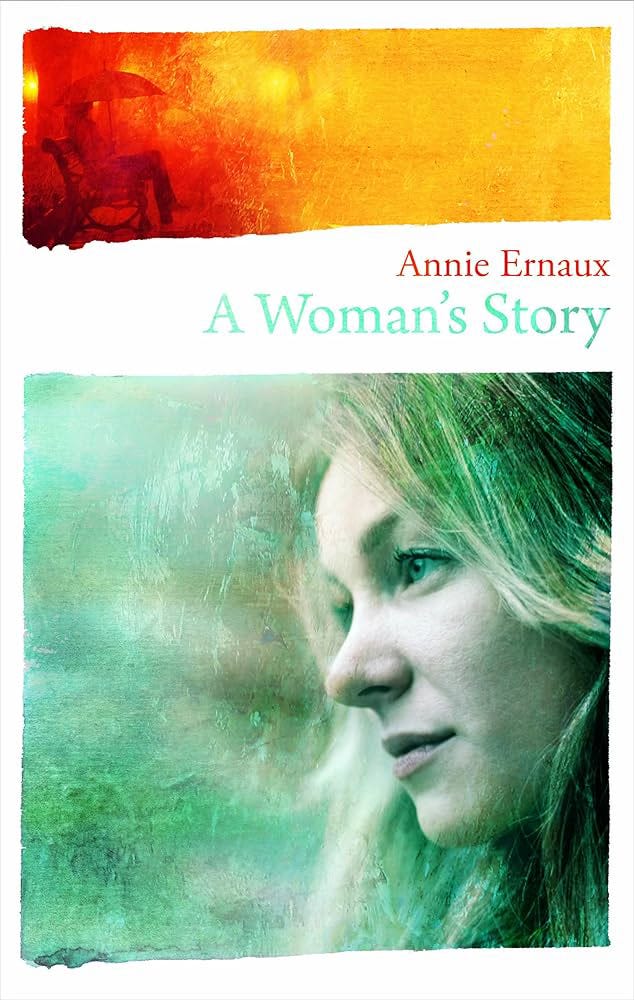

“Naturally, this isn't a biography, neither is it a novel, maybe a cross between literature, sociology and history. It was only when my mother - born in an oppressed world from which she wanted to escape - became history that I started to feel less alone and out of place in a world ruled by words and ideas, the world where she had wanted me to live.”- from “A Woman’s Story” by Annie Ernaux. Translated from the French by Tanya Leslie. (Quartet. 1988)

Another staggering text from Ernaux that as ever leaves nothing for her or us to hide behind, so unbearably moving but also brilliantly objective is her point of view that at times I found myself wincing, laughing and crying all within seconds of each passing sentence.

Breathtaking.

“I shall never hear the sound of her voice again. It was her voice, together with her words, her hands, and her way of moving and laughing, which linked the woman I am to the child I once was. The last bond between me and the world I come from has been severed.” - from “A Woman’s Story” by Annie Ernaux. Translated from the French by Tanya Leslie. (Quartet. 1988)

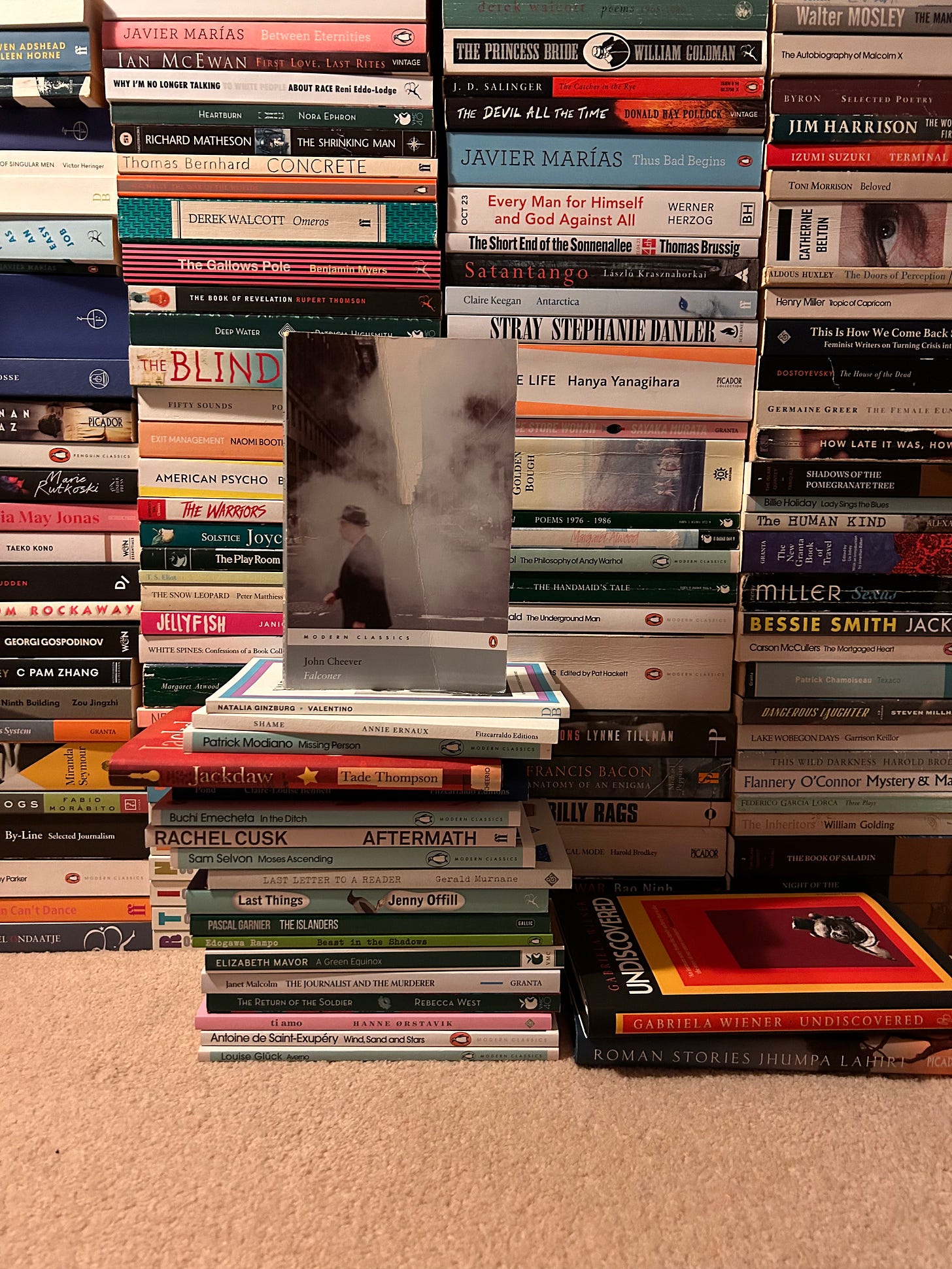

“The main entrance to Falconer - the only entrance for convicts, their visitors and the staff - was crowned by an escutcheon representing Liberty, Justice and, between the two, the sovereign power of government. Liberty wore a mobcap and carried a pike. Government was the federal Eagle holding an olive branch and armed with hunting arrows. Justice was con-ventional; blinded, vaguely erotic in her clinging robes and armed with a headsman's sword. The bas-relief was bronze, but black these days - as black as unpolished anthracite or onyx. How many hundreds had passed under this, the last emblem most of them would see of man's endeavor to interpret the mystery of imprisonment in terms of symbols. Hundreds, one guessed, thousands, millions was close. Above the escutcheon was a declension of the place-names: Falconer Jail 1871, Falconer Reformatory, Falconer Federal Penitentiary, Falconer State Prison, Falconer Correctional Facility, and the last, which had never caught on: Daybreak House. Now cons were inmates, the assholes were officers and the warden was a superintendent. Fame is chancy, God knows, but Falconer - with its limited accommodations for two thousand miscreants - was as famous as Newgate. Gone was the water torture, the striped suits, the lock step, the balls and chains, and there was a softball field where the gallows had stood, but at the time of which I'm writing, leg irons were still used in Auburn. You could tell the men from Auburn by the noise they made.” - from “Falconer” by John Cheever. (Penguin Modern Classics. 1977)

I’m a big fan of prison novels and have read plenty of them, I’m also a big fan of John Cheever but for some crazy reason I had no idea that “Falconer” was in any way what it actually is.

Falling into the areas of the literature of incarceration inhabited by writers like Genet and novels like “Hard Rain Falling” this masterpiece is a poetic, ferociously beautiful, morally destitute piece of work that was as strangely moving as it was audacious.

Cheever was a master at describing the conflicts between the inner and outer worlds of human beings and the brutal nature of families riven with violence and mendacity, and it’s effects, subtle, profound on its players. All of these skills, and then some, are on display here to devastating effect.

“At first, I thought the black birds were crows but I was mistaken. They had to be closer to cormorants, maybe shags. Gathered by the edge of the water, far from where I was standing on the bridge, I could see some of them, clumped together, staring at the factory. They looked slick as oil, like if you wrung one by the neck you'd get black ink all over your hands. They were floating in brackish water, where the river spills into the ocean. But do shags live in places like that? Are they ocean birds? River birds? I wiped the sweat from my forehead.” - from “The Factory” by Hiroko Oyamada. Translated from the Japanese by David Boyd. (Granta. 2023)

A real master of the narrative of bewilderment, miscommunication and opaque banalities, Oyamada here goes all out as far as challenging form goes, which certainly infused in me a solid sense of unease, confusion but also an uncommon excitement.

I love books about work, occupation, the time we spend earning our living; “The Factory” in many ways sums up the mutual absurdities of an organisation and the people who toil within it, their personal codes juxtaposed next to the codes of the company, and also to greatly surprising effect here, the animals who share the space with them.

The mysterious birds who gather at the river running through the complex and the coypus who live in its drains all somehow contribute to the open-ended nature of the horrors of the gig economy that many of us work in to survive.

Very strange, thrillingly challenging, highly recommended.

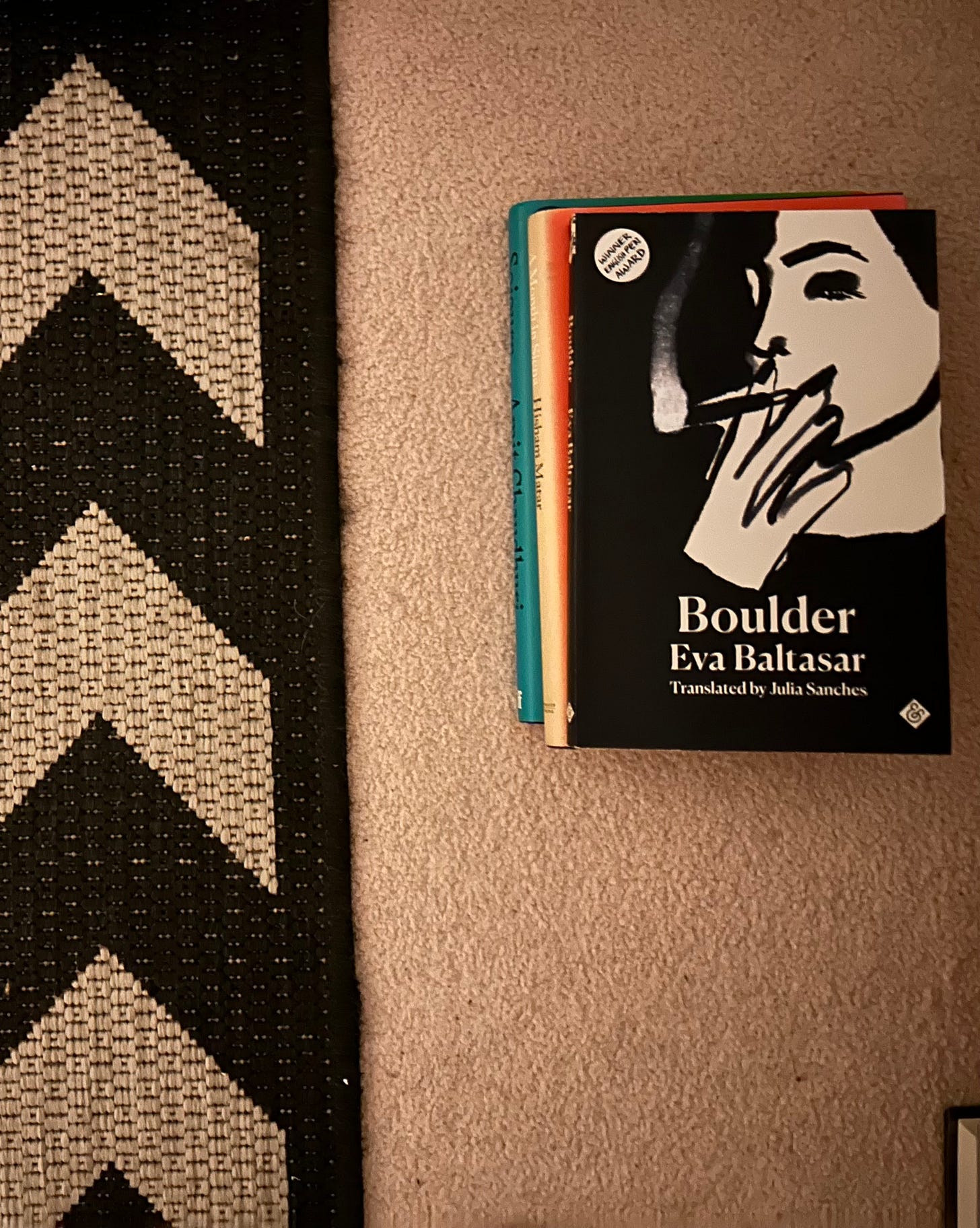

“What was I thinking, dropping everything? The devastating possibility of the same old job, of a tiny room in a suburban apartment, of lovers as fleeting as shooting stars, hot to the touch one day, a distant dream the next. The days came and went, unchanging, and every night I tossed them back one swig at a time, stretched out on my narrow bed with headphones in my ears and an ashtray on my chest. I'd gone through life fixated on an intangible conviction, tied down by the handful of things that kept me from becoming penniless, an outcast. I needed to face the emptiness, an emptiness I had dreamed of so often I'd turned it into a mast, a center of gravity to hold onto when life fell to pieces around me. I'd come from nothing, polluted, and yearned for windswept lands.” - from “Boulder” by Eva Balthasar. Translated from the Catalan by Julia Sanches. (& Other Stories. 2022)

A raging, erotic, poetic and moving story of queer motherhood, rootlessness and transience from a writer of a very different vision, power and guts.

Certainly deserving of the attention garnered, I’ll be doubling back to read the first volume, this being the second, of this, Balthasar’s thematic trilogy of first person female narratives.

Ferociously moving.

“That must surely be the ambition of every reunion, not only to identify and be identified, but also to have an accurate account of all that has come since the last encounter. And it must surely follow that what lies behind our longing and nostalgia is exactly this need to be accounted for. It is as if what Di Paolo is thinking here is that a true hell is not the hell of fire but of not being recognised by those closest to us. We want to be seen by them and, in turn, rediscover our own powers of remembrance, and to finally find the consolation that lies between intention and expression, between the concealed sentiment and its outward shape. The painting understands this. It knows that what we wish for most, even more than paradise, is to be recognised; that regardless of how transformed and transfigured we might be by the passage, something of us might sustain and remain perceptible to those we have spent so long loving. Perhaps the entire history of art is the unfolding of this ambition; that every book, painting or symphony is an attempt to give a faithful account of all that concerns us.”- from “A Month in Siena” by Hisham Matar. (Viking. 2019)

Matar is an extraordinary literary figure, not only possessor of one of the purest prose styles of any writer living or dead, he also has a razor sharp sensibility in regards to his place in the world.

“The dream was of a family living in a large and windowless room. If he, the old man, does not cook supper, then his wife prepares the same meal they eat every night before they turn in: boiled eggs, a plate of tuna and harissa, bread, sliced cucumber sprinkled with salt. The elderly couple have a child, a boy. He is theirs but because of the large age difference does not seem to belong to them completely. And, notwithstanding his good temperament, the boy has that particular sadness of the children of ageing parents. His old father tries to keep up a degree of good cheer on Fridays, when after prayer he takes a small chicken out of the freezer. Half a cup of sugar, another of salt, a splash of vinegar, all mixed in a large pot. He then fills it with warm water and sinks the bird into the brine to clean it, hearing the bubbles escape. The father does all of this with an automatism that conveys the simple pleasure he finds in these steps but also a hesitant regret, some deeply private remorse. What has remained most strongly with me from the dream is not its narrative but rather its frugal atmosphere, the silence that accompanied the lives of these people.”- from “A Month in Siena” by Hisham Matar. (Viking. 2019)

His father was a Libyan political exile living in London, when Matar was 10, on a family holiday in Egypt, his father was kidnapped and disappeared by the Libyan secret service, never to be seen again. Unsurprisingly this unimaginable event haunts his life and much of his work. The not knowing must be crippling, but it has inspired one of the finest novels of the last 50 years “The Anatomy of a Disappearance”, a fictionalised account of that very event.

“I exist mostly to one side of time. Only in rare moments-for example, when I am with those I love or in times of great exuberance or when I am writing and the work is going well - do I feel in time, that I am where I am meant to be and utterly free from the wish to be anywhere else. The other times have the interference of discord, as though I were detained and that somewhere nearby, possibly in the next street, there is a desired encounter or event taking place, one from which, whether by coincidence or ignorance or bad luck, I am being excluded. The strange thing was that I never suffered this in Siena. Every day and for the entire month I spent there I felt myself to be in time. I woke up at the right moment and left the flat just at the perfect instant so as to encounter everything that unfurled before me.”- from “A Month in Siena” by Hisham Matar. (Viking. 2019)

This book is something else entirely. Part travelog, part mediation of otherness and being alone in an ancient city, and most surprisingly part art history, this amazing book represents also a letting go of sorts of the memory of his fathers abduction, itself an act of extreme bravery.

“Since as far back as I can remember, I have caught myself imagining the quality of certain known rooms when empty: our old dining room in Tripoli in the house where we lived until I was eight, my current writing studio in London when I am not in it, a close friend's place, much frequented galleries in familiar museums. All the lights are switched off and the curtains drawn, yet the furniture and books and pictures all hold their ground, waiting with an intimate patience, a patience that stares desolation in the eye. I do not know why I do this. But in Siena, where I felt I had arrived at the edge of things, the high-ceilinged rooms of my flat, rooms older than me, older than entire cities elsewhere, seemed to have been always waiting for me. Their atmosphere, which I detected from the very first moment I entered the place, was of that unobservable emptiness I had sought all these years.” - from “A Month in Siena” by Hisham Matar. (Viking. 2019)

“There are spaces in which you sense time, but also inhabit the viewpoint of those who've already been there. You see through the eyes of those who've gone. These perspectives are intense but momentary.” - from “Sojourn” by Amit Chaudhuri. (Faber. 2023)

Reminiscent of the original, fragmented and liminal spaces in writing that W. G. Sebald and Rachel Cusk inhabit, Chaudhuri deals in specifics of personal, physical and emotional information with a gimlet but bemused eye, full of sharp charm and intelligence.

Set in the academic world of Berlin some 15 years after the wall fell, the backdrop of a shifting landscape of history underpins this narrative, creating a brilliantly illustrated sense of intangibility and unease, from the point of view of a man subtly out of place.

“He gave you food; he stood next to you in solidarity when you tried on jackets; he would have shared cigarettes and his flat if I'd been a smoker or needed a room; he might offer his woman. He didn't create a boundary round himself, saying, 'This is mine; not yours.' As long as he was with you, he was in a state of transport.” - from “Sojourn” by Amit Chaudhuri. (Faber. 2023)

A very fine act of brevity, shifting landscape and our collective understanding and misunderstanding of each other.

That’s November. Thanks for looking.